Heartbeat: Life, Choice, and Abortion.

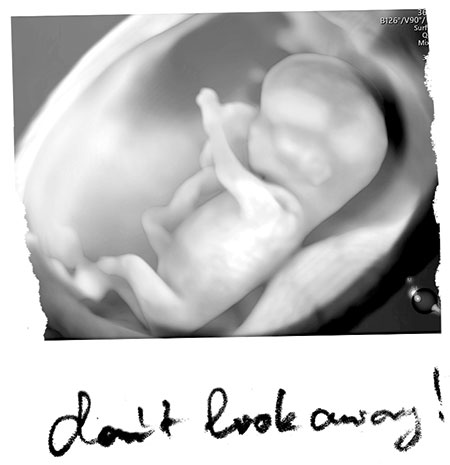

When does life begin? This question might mean different things to, say, a teen-ager, yearning for excitement; or to a middle-aged man, driving a Porsche, groping towards some long-elusive “purpose.” But in the context of the abortion debate, this question takes on a greater weight. When does life begin? When does the union of two cells, one maternal and one paternal, become one human being? How can the inception of human life, the moment of miraculous awakening, be measured?

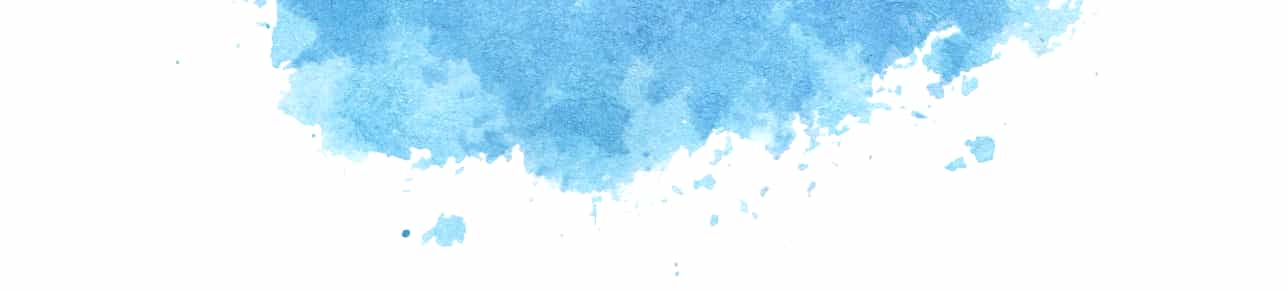

For many supporters of the pro-life movement, the answer is simple and decisive: life begins with a heartbeat. (The heart is the first organ to develop in utero; it begins beating spontaneously around 21 or 22 days after conception.) Anti-abortion adherents believe that an embryo is no longer a mass of unconscious cells, but a human being, at the moment its pulse is detected. This claim is loosely philosophical, but its striking emotional resonance is compelling. For some, it is a spiritual proposition. And from the pro-life perspective, a foetus is a person from that moment onward; as such, it has a right to life.

On the other side of the debate, this reasoning tends to be carefully avoided. The pro-choice camp generally emphasises other legitimate aspects of the ethical dilemma, and understandably so: negating the “heartbeat” argument is a squeamish prospect that would be at odds with the pro-choice cause. But a host of personal and medical imperatives for abortion deserve sober consideration, including the notion that a woman should have autonomy over her own body; that she should have the power to choose what occurs within it; that she should have the ability to decide whether to carry a child conceived of rape or incest; that she should be able to assess her own personal and economic stability, as well as that of her environment, while considering whether to bring forth a child; that she should have access to life-saving treatment should her pregnancy endanger her own well-being.

Nineteen seventy-nine marked the final year of Cambodian tyrant Pol Pot’s five-year genocide, which resulted in the slaughter of nearly two million civilians, or a quarter of Cambodia’s population. (Bear with me.) It was the year of Saddam Hussein’s purge of the Iraqi Ba’ath Party, which, in Stalin-esque fashion, paved the way to his own absolutist reign. It was the year, too, of the All Saints’ Massacre in Bolivia, during which more than a hundred peaceful protesters were liquidated for opposing the dictatorship of Alberto Natusch Busch. Yet, in her acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize of that year, Mother Teresa claimed that “the greatest destroyer of peace today is the cry of the innocent unborn child.”

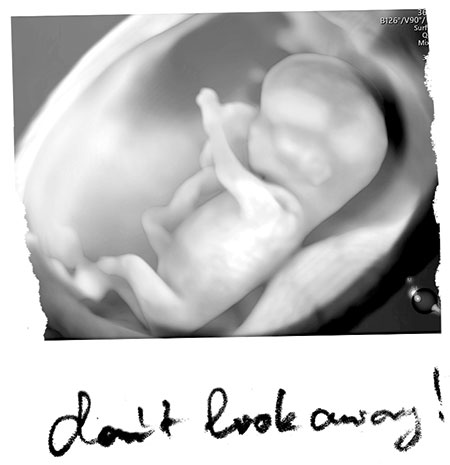

Less than twenty years later, Bill Clinton (of all people) claimed that abortion should be “safe, legal, and rare.” Clinton’s slogan, though memorable, has become unfashionable in this moment of uncompromising partisanship. Instead, we have, on one hand, the assertion that abortion is tantamount to murder; on the other, that women who have abortions should do so without “sadness, shame or regret.” What is lost amid the zealousness of the current debate is a note of subtlety, and an admission, on both sides, of the nuances that surround abortion.

In essence, the dispute over abortion can be reduced to a single question. Which is the more significant moral priority: the potential for life, or the persistence of life? Or, to put it bluntly, which life deserves greatest consideration: a child’s, or a woman’s? Yet it deserves more thought than what little is demanded of a simple, unreflecting adherence to ideology, religion, or party.

Both extremes contain paradoxes and hypocrisies. Nowhere else does the right-wing defend so fervently (or at all) the necessity for state intervention in private life. Nor does the left-wing demand as strongly in any other sphere that the individual be left alone by the rights-thieving hands of the government. An anti-abortion activist might ask of the typically progressive pro-choice faction: Why is the extinction of myriad species, and the health of the planet itself, of so much apparent concern, but not the lives of unborn children? Why does the termination of animal life, but not of developing human life, inspire unease?

Meanwhile, an abortion-rights campaigner may equally demand to know how the broadly reactionary pro-life movement can reconcile an obsession with preserving life with an ideology that is in favour of unforgiving law-and-order policies, aggressive military intervention, and the death penalty; that is against gun control, immigration, and welfare, as well as other measures designed to alleviate the worst effects of hereditary poverty. Pro-life—until the moment of birth. But where is the care for life beyond birth? Pro-life—but for an unmerciful type of life that excludes all but the most primitive notion of justice.

What can the pro-life movement offer to mothers? Its uncompromising stance seems to hang disadvantaged, violence-prone mothers out to dry: no matter how few necessities a woman is able to afford for her child, no matter how battered and bruised, no matter (for fundamentalists) if she is forcibly impregnated, she is shown no mercy. She must raise her child despite the horrors she has faced; despite the horrors her child may be likely to face. Is this truly an attitude of compassion, as is asserted in pro-life circles?

What can the pro-choice side offer to the concerned conscience? While a vulnerable child raised in destitution is a pitiable figure, is not its chance of a decent life great enough to silence any justification for violating life’s sanctity? Is not the possibility of a child’s overcoming difficult circumstances, and achieving some joy, enough to make the denial of that chance seem cruel and unjustified? Does the approval of abortion not imply a reckless and dubious assumption of moral authority—the authority to end a new life? Pro-choice—but whose choice is it to make?

The pro-life movement fixates on the “dignity” of unborn children. Here, we find the most specious, insincere aspect of the anti-abortion doctrine. The sanctimonious appeal to dignity is deceitful and designed to cast abortion proponents as amoral, in contrast to the broadly Christian notion of morality that many disciples of pro-life share.

These apostles would do well to swallow their own medicine, and revisit the words of Jesus himself: “If a brother or sister is naked and destitute of daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Depart in peace, be warmed and filled,’ but you do not give them the things which are needed for the body, what does it profit? Thus also faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead” (James 2:15–17). In other words, practice what you preach. If pro-life preaches compassion, then it must also demonstrate compassion in order to uphold the legitimacy of its position. Pro-lifers lose all credibility in limiting their empathy to the womb. They do not extend it to those whom they would otherwise prevent from having abortions—all those mothers and families who struggle every day to maintain their dignity in the face of hatred and violence, at the mercy not just of an indifferent world but of pro-life activists themselves. When opponents of abortion no longer debase themselves (to say nothing of the women they besiege), they can sermonize more honestly about “dignity.”

Pro-choice faces its greatest pitfall in its failure to provide a compelling counterargument to assuage anxieties surrounding, so to speak, the “heartbeat” of the abortion debate. Its rhetoric has been criticized for “dehumanizing” what pro-lifers prefer to call “unborn children,” by referring to them instead as foetuses, lumps of tissue, or collections of insensate cells. These criticisms stem from a reluctance on the part of the pro-choice camp—which portrays abortion as a routine matter of healthcare—to acknowledge the moral gravity of abortion. For critics, a discussion of abortion without this sort of concession is unfeeling and disrespectful. But pro-choice advocates have done little to dispel these accusations. What must be admitted is that abortion-rights activists do take a utilitarian approach to morality: they may recognize abortion as unsavoury, but, given certain preconditions, see a greater ethical priority in protecting a mother’s interests. This is a credible position that pro-choice is nevertheless loath to defend. In avoiding an honest discussion, the pro-choice movement has allowed detractors to define what it believes—that abortion advocates, who are inhumane, do not care about foetuses (or, if you prefer, the unborn), and do not flinch at the idea of abortion. The public, however, deserves to know what pro-choice truly represents.

Join the Third Force Collective to access our revolutionary briefings.

This isn't a paywall. You can close it if you just want to read the article below it. But our aim is to win the planetary endgame — we want to catalyze a moment of truth, a stunning reversal of perspective from which corpo-consumerist forces never fully recover. For that we need you.