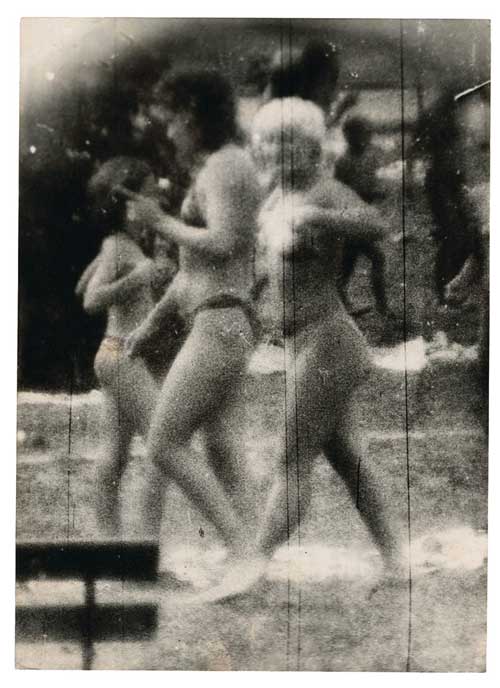

The world is bright. The sun shines, tempting you to idle by a sleepy Moravian town’s only swimming pool. The day’s balmy embrace leaves your skin aglow, as if with its own modest radiance. As you approach the poolside, a tepid breeze half-heartedly churns the dust on the road and stirs the leaves on the trees into a chorus of hushed murmurs. The sunlight breaks gently through the branches, casting a mottled patchwork of glimmering shade onto the encircling lawn. The crowd at the water’s edge moves about indifferently, languid and lazy as the day. It is as if nature has conspired to render the world benign and comfortable for your benefit.

As you begin to undress, revealing the swimsuit beneath your summer frock, a vague shadow appears beyond the chain-link fence. Its darkness is striking amid the bright of day. As it emerges from between the tree-trunks, its shape becomes discernible: it is a man’s, squalidly attired, with a disheveled beard and matted hair. In his filthy hands, he holds a crude object assembled from shards and lumps of discarded material. A cylinder, perhaps a cardboard tube, projects outwards from the thing; he holds it up to his eye like a makeshift camera. Wordlessly, as if unnoticed, he apes taking your picture, and smiles a vagabond’s grin.

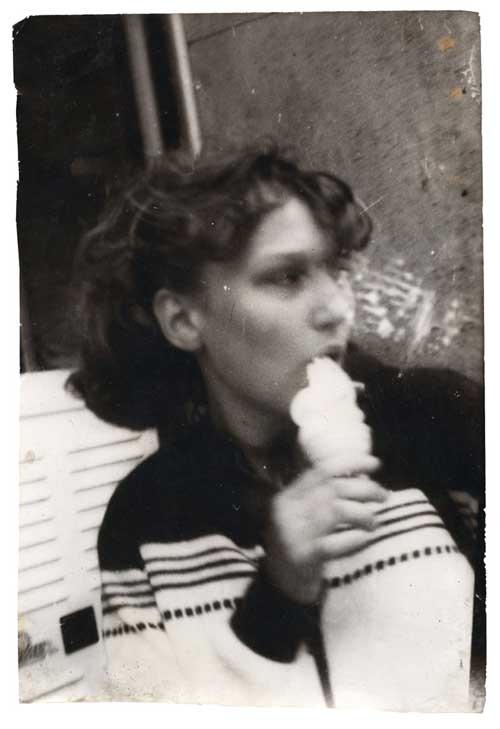

The town is Kyjov, in the southeast of the Czech Republic; the man is Miroslav Tichý; and the camera, in fact, is real. During some twenty years, from the 1960s until the 1980s, Tichý took tens if not hundreds of thousands of ghostly photographs, mostly of unsuspecting women, with primitive cameras that he made from whatever he had at hand. For lenses, he used Plexiglas, ground and polished with toothpaste and cigarette ash; for shutter mechanisms, spools of wood and ribbons fashioned from the elastic waistbands of threadbare underwear; for rewind knobs, caps from beer bottles; for mounts, wood or cardboard.

The resulting images are, in the words of Tichý’s onetime neighbour, Roman Buxbaum, “underexposed or overexposed, out of focus, made from scratched negatives, developed on paper that is either cut by hand or even torn.” They feature women (or their disembodied, eroticized parts) of all ages, in haphazard scenes of everyday life, in the streets and parks of Kyjov. A few of the subjects, flattered, smile or pose spontaneously; others scowl into the lens. Most seem to be caught unawares, the captor of their images peering at them surreptitiously, at a distance. Tichý’s brutal post-production treatment of his photographs — which, according to Buxbaum, included “dust and dirt on everything, filth in the camera and in the darkroom, finger prints [sic], bromide stains, places gnawed by rats and silverfish” — only adds to their haunting, forlorn, and foreboding character.

“When I was a little boy,” recounts Buxbaum, “my grandmother used to say: ‘Wash your hands! Otherwise you’ll be like Mirek Tichý!’ For my grandmother, Tichý was a prime example of what not to be.” In 2005, Kyjov’s then-mayor, while admiring some of Tichý’s photographs in Zürich, explained that he had known of Tichý since his childhood (“since I went to the swimming pool,” where Tichý was forbidden to enter), when fellow children thought of Tichý as a frightening, spectral presence. Believing his cameras to be false, they bought into the local folklore, which described Tichý as a sort of madman. “Now” that the mayor could appreciate his work, “I would like to take my hat off to him.”

Notoriety came late to Tichý. The accumulating results of his prodigious, years-long project were discovered only in 1981, when Buxbaum (who has made a short documentary, Tarzan Retired, about Tichý), was permitted, after more than a decade of exile, to return to Kyjov from Switzerland. (Buxbaum’s family had escaped Czechoslovakia during the Soviet invasion in 1968.) And it was not until 2004 that Tichý’s photographs were exhibited for the first time, at the International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Seville. Larger, solo exhibitions — such as those in Zürich, Paris, and New York (in 2005, 2008, and 2010 respectively) — helped to garner ever wider appreciation for his work.

By then, Tichý had long ceased to take photographs: “I had a planned number I wanted to do: I would make such and such a number a day, such and such a number in five years, and when I did it, I quit,” sometime in the mid-1980s. But even longer before, he had renounced another artistic calling. In 1945, Tichý attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, where he painted in the modernist style of the prewar era. But after the Communist coup in 1948, Tichý’s freedom to paint was severely restricted. He refused to depict the narrow, political subjects that the Communists censors demanded, and dropped out of the Academy.

Then began a period of crisis, disillusionment, and passive resistance. Strangeness and nonconformity made him a suspicious figure in the eyes of the authorities. “He was the opposite,” in Buxbaum’s view, “of the ideal new Socialist man.” His previous treatment at a psychiatric hospital (psychiatry being an infamously abused instrument of Soviet and Soviet-allied persecution), paired with his increasingly shambolic appearance, gave police sufficient pretext to periodically incarcerate Tichý — purportedly to “normalize” him, in accordance with ideological standards — in a psychiatric clinic. He would return a few days later, shaven and bathed, only for the abuse to repeat itself, mostly at the occasion of political holidays. Tichý came to accept his lot, readying a small suitcase before each predicted visit of the police. He stoutly refused, however, to accept normalization.

Tichý came to rent an attic in the home of Buxbaum’s grandmother, and therein set up a studio. But when the home was nationalized, he was threatened with eviction, the space that he occupied having been intended for the use of a collective of leather-goods menders. Standing his ground, Tichý was forced out for “economic-political, social, and also security reasons.” His paintings were cast into the street; he never painted again. But his creative spirit adapted. “The Stone-Age photographer was the embodiment of an insult to the small-town Communist elite,” wrote Buxbaum. “He became the living antithesis of progressive thought, of the Marxist theory of history moving in a straight line.”

What is one to make of Tichý? Do his photographs truly smack of artistic ingenuity, or are they simply the product of serendipitous chance? Is the element of the voyeuristic, the intrusive in his gaze to be excused on the grounds of its aesthetic merits? Tichý certainly had no illusions as to his talent: “If you want to be famous, you have to do something so badly that no one else in the world does it as badly!” As to the erotic: “That always [meant] police, prison and mental institutions.” Perhaps to escape or subvert those bonds, Tichý saw his only recourse in surveillance, in the forbidden look — in an undetectable glance so alike to that of his tormentors. Whatever the truth may be, Tichý offers at least one instructive example: under conditions that are hostile to self-expression, the last refuge of the artist lies in affirming the banal, the workaday, the commonplace poetry of life. In a world that is brutalized and on fire, we may well be forced to cobble together our own creative tools from the debris and rubble. And, in face of it all, may we affirm the simple beauty of our raw humanity: it may be all that we have left.

Miroslav Tichý photos courtesy Tichy Ocean