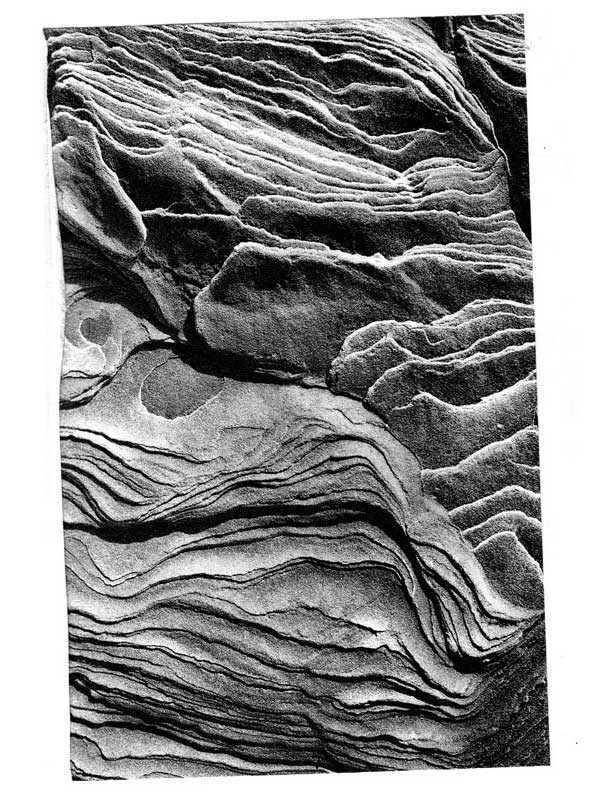

Look up on a cloudless night and you might see the light from a star thousands of trillions of miles away, or pick out the craters left by asteroid strikes on the moon’s face. Look down and your sight stops at topsoil, tarmac, toe. I have rarely felt as far from the human realm as when only ten yards below it, caught in the shining jaws of a limestone bedding plane first formed on the floor of an ancient sea.

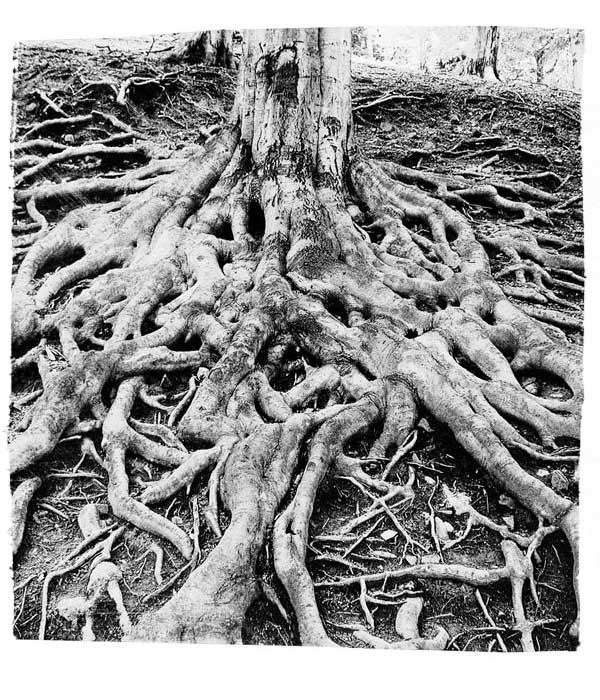

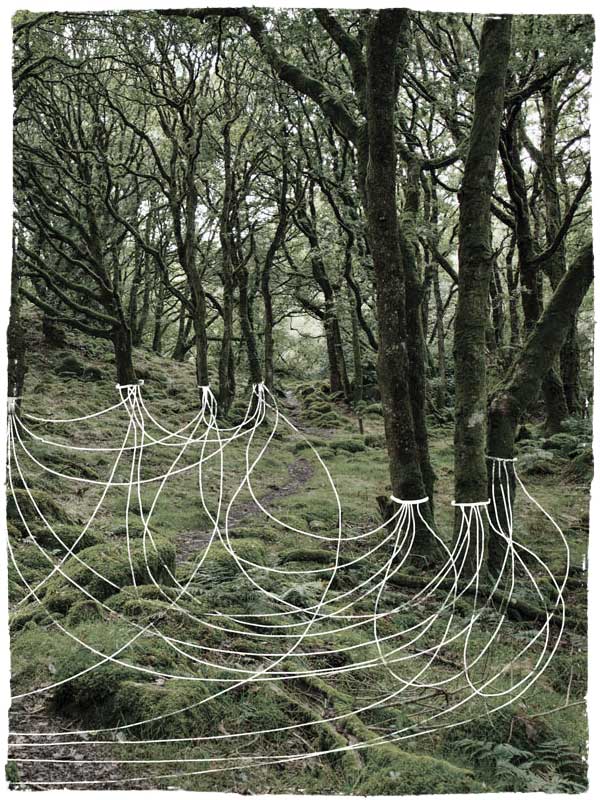

The underland keeps its secrets well. Only in the last twenty years have ecologists succeeded in tracing the fungal networks that lace woodland soil, joining individual trees into intercommunicating forests

— as fungi have been doing for hundreds of millions of years. >>

We are presently living through the Anthropocene, an epoch of immense and often frightening change at a planetary scale, in which ‘crisis’ exists not as an ever-deferred future apocalypse but rather as an ongoing occurrence experienced most severely by the most vulnerable. Time is profoundly out of joint — and so is place. Things that should have stayed buried are rising up unbidden. When confronted by such surfacings it can be hard to look away, seized by the obscenity of the intrusion.

In his book Vertical, Stephen Graham describes the dominance of what

he calls the ‘flat tradition’ of geography and cartography, and the ‘largely horizontal worldview’ that has resulted. We find it hard to escape the ‘resolutely flat perspectives’ to which we have become habituated, Graham argues — and he finds this to be a political failure as well as a perceptual one, for it disinclines us to attend to the sunken networks of extraction, exploitation, and disposal that support the surface world.

Yes, for many reasons we tend to turn away from what lies beneath. But now more than ever we need to understand the underland.‘Force yourself to see more flatly,’ orders Georges Perec in Species of Spaces. ‘Force yourself to see more deeply,’ I would counter. The underland is vital to the material structures of contemporary existence, as well as to our memories, myths, and metaphors. It is a terrain with which we daily reckon and by which we are daily shaped.Yet we are disinclined to recognize the underland’s presence in our lives, or to admit its disturbing forms to our imaginations. Our ‘flat perspectives’ feel increasingly inadequate to the deep worlds we inhabit, and to the deep time legacies we are leaving.

— Robert Macfarlane, Underland

A global movement is gaining momentum that grants legal personhood to rivers, lakes, forests, and mountains. It is just one element of a controversial new animism by which writers, scholars, lawyers, and politicians are radically reassessing our place in the natural world.

— Robert Macfarlane

On 26 February 2019, a lake became human. For years, Lake Erie — the southernmost of the Great Lakes — has been in ecological crisis. Invasive species are rampant. Biodiversity is crashing. Each summer, blue-green algae blooms in volumes visible from space, creating toxic “dead zones”; the algae is nourished by fertiliser and slurry pollution from surrounding farms. In August 2014, phosphorus run- off so fouled Erie that the city of Toledo, at the lake’s western tip in Ohio, lost drinking water for three days in the hottest part of the year.

Appalled by the lake’s degradation, and exhausted by state and federal failures to improve Erie’s health, in December 2018 Toledo City councillors drew up an extraordinary document: an emergency “bill of rights” for Lake Erie. At the bill’s heart was a radical proposition: that the “Lake Erie ecosystem” should be granted legal personhood, and accorded the consequent rights in law — including the right “to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve”.